It was 1997, and I was twenty-seven and walking around like the legal system had personally issued me a backstage pass.

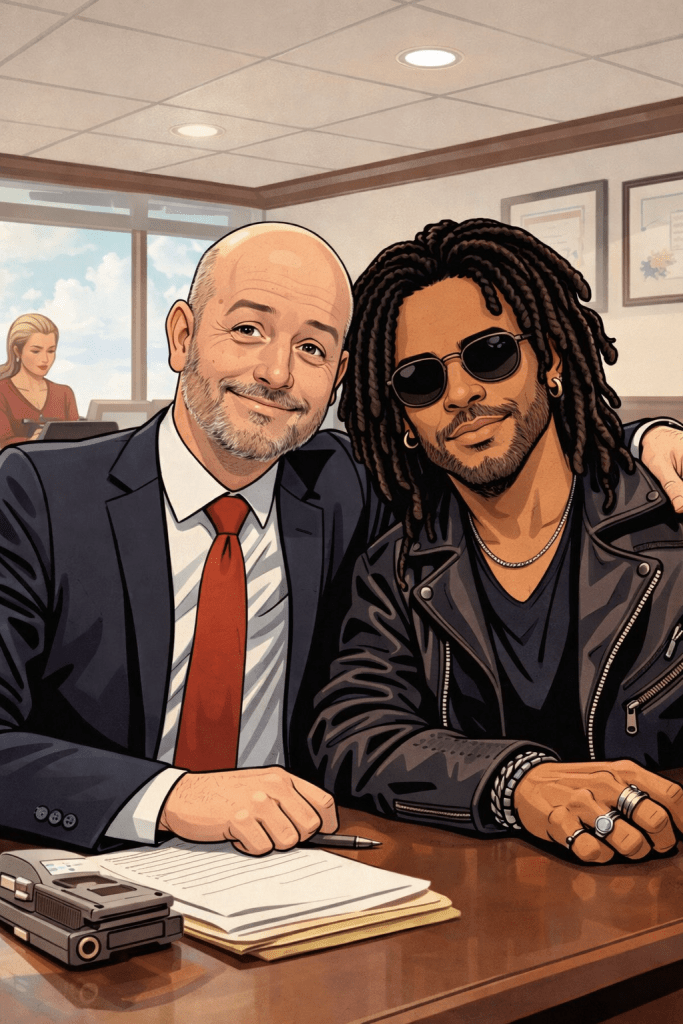

One of my first “real” assignments had landed in my lap like a dare: a deposition involving rock star Lenny Kravitz and the ownership of a Magnum yacht.

Not a dinghy. Not a polite little cruiser.

A Magnum.

I remember rehearsing the opening in my head all the way to the conference room: calm voice, controlled tempo, no fanboy energy. I told myself I’d be professional. I told myself I’d treat him like any other witness.

And then he walked in.

Leather jacket like armor. The whole room subtly recalibrated around him. Even the air-conditioning seemed to lower its voice.

The court reporter blinked twice like she was buffering.

Opposing counsel stood up, hand extended, trying to look unfazed, which—if you’ve ever watched an attorney attempt “unfazed” in front of a celebrity—is like watching a cat pretend it didn’t just fall off a counter.

I stood, too. Smooth. Confident. Young-cocky-attorney smooth.

“Mr. Kravitz,” I said, as if this was totally normal and not a surreal moment that my seventeen-year-old self would have built a shrine around. “I’m Eddie Stephens. I’ll be asking you some questions today.”

He nodded once, polite, unreadable. A man who’d been interviewed by better and louder than me.

We all sat. The court reporter swore him in. The red light of the recorder came on like a tiny stage spotlight.

And there it was, that moment you learn as a baby lawyer: the second the record starts, you either become a professional… or you become a story someone tells at happy hour for the next twenty years.

I cleared my throat.

“Mr. Kravitz, do you understand you’re under oath today?”

“Yes.”

“Have you ever had your deposition taken before?”

A brief pause. “Yes.”

I slid into the topic. Ownership. Title. Registration. Purchase details. How the transaction was structured.

And then we got to the heart of it—why this boat, why this builder.

“Why did you choose a Magnum?” I asked, making my voice sound like it had asked this question a thousand times before, to a thousand non-famous people.

He leaned back slightly. “I’m into design,” he said, like that explained everything. “The style. The lines. The architecture. That mattered first.”

He spoke with this quiet certainty—like he’d already answered the question for himself years ago and was just sharing the conclusion.

“And speed?” I pressed.

Now his smile grew a fraction. “Speed matters. I don’t get a lot of time to just… disappear. With that boat, I can run out to Bimini for lunch and still be back with enough time to do real work.”

Bimini for lunch.

I’d had peanut butter crackers for lunch.

And for a second, my cocky attorney brain shut up, and some deeper part of me understood: the boat wasn’t a flex. It was a door.

Which is exactly why my brain did the dumbest thing it has ever done in a deposition.

Because along with being a “young prodigy,” I was also, apparently, an idiot with a plan.

My secret mission had been simmering since the moment the file landed on my desk: Get the autograph.

Not by asking. That would be too honest.

No—my plan was slick. Lawyerly. Technical. I told myself it was “strategic.”

The contract had a signature. We needed to authenticate it. We needed to confirm it was his. We needed… a comparison.

A writing sample.

And I had convinced myself that if I could just get him to write a few lines on the record—purely for legal purposes, of course—then I’d have a little piece of rock history in my file.

So I slid the contract across the table, maintaining my most innocent tone.

“Mr. Kravitz, I’m going to show you what’s been marked as Exhibit 4,” I said. “Do you recognize this document?”

He glanced down. “Yes.”

“Is that your signature on page three?”

“Yes.”

I nodded, very serious. “For the record, we need to confirm authentication. Would you be willing to provide a brief writing sample—just a few words—so the signature can be compared?”

Opposing counsel’s head tilted, just slightly, like a dog hearing a strange noise.

Lenny looked at me, then at the paper, then back at me.

“What kind of sample?”

“Oh—anything,” I said quickly, too quickly. “Just… your name, maybe today’s date.”

I produced a clean sheet of paper like a magician producing a dove.

Opposing counsel’s eyes narrowed.

Lenny took the pen.

And that’s when I felt it—the thrill of the absurd. The secret victory. The smug inner monologue: You’re brilliant, Eddie. Twenty-seven and already out here playing chess while everyone else plays checkers.

He wrote calmly. A few strokes. Smooth and quick, like he’d signed a thousand things that week alone.

Then he slid the paper back.

I glanced down.

There it was.

My trophy.

My brain went full goblin: Pocket it. Pocket it now.

I reached to gather the exhibits, and my hand—my traitor hand—hovered just a fraction too long over the writing sample.

Opposing counsel cleared his throat.

“Counsel,” he said, dry as legal dust, “that writing sample is now part of the record. It stays with the exhibits.”

The court reporter didn’t look up, but I swear I felt her smiling.

Heat rose up my neck like a curtain falling.

“Of course,” I said, too brightly. “Naturally. For the record.”

I tried to recover my dignity by shuffling papers with the intensity of a man organizing his way out of shame.

Lenny didn’t laugh. He didn’t smirk. He just looked at me—one long, calm look—like he knew exactly what I’d tried to do and had decided I was harmless.

Then, with a kind of quiet mercy, he said, “You’re young.”

The words weren’t cruel. They were accurate. Like a doctor noting a symptom.

I swallowed. “Yes, sir.”

He leaned forward a little. “You’re doing fine.”

And that was the moment I learned the strangest truth of being a young lawyer: you can be cocky, you can be sharp, you can even be good—

—but every once in a while, the universe puts a rock star in a conference room to remind you that you’re still just a kid with a pen, trying to look like you belong at the table.

We finished the deposition clean after that. Ownership clarified. Magnum details nailed down. The record tidy. The case moved forward.

And as he stood to leave, he paused at the door.

He looked back at the table, at the exhibits, at my too-shiny suit and my too-eager face.

“Enjoy the ocean when you can,” he said, almost casually. “Otherwise the world will eat all your time.”

Then he was gone.

I sat there staring at the empty chair, the writing sample safely imprisoned in the exhibit stack—forever out of my pocket, forever on the record.

I didn’t get the autograph.

But I got something else:

A story.

A lesson.

And, for the first time in my career, the faint suspicion that maybe the real flex isn’t owning a Magnum 60—

it’s knowing how to disappear into your own life long enough to hear yourself think.

Leave a comment