At some point in the middle of my career, I got the itch.

Not the “buy a motorcycle and pretend I’m twenty-five” itch.

One that whispered;

Maybe it’s time to be part of something bigger than you.

I had built a name. Built a practice. Built momentum. But there was a part of me that wanted to attach my work to an organization that felt… larger. A machine. A flagship. A place where I could say, I’m not just Eddie Stephens out here doing Eddie Stephens things… I’m part of a legacy.

And there was one firm in West Palm Beach that always seemed to be hovering in my orbit.

They had been wooing me for a while… subtle, steady, confident. I’d get the occasional friendly invite, the flattering nods, the “we should talk sometime” energy.

Then they invited me to their Christmas party.

Now listen… some people get hired because of resumes, grades, publications, trial records, board certifications.

I got sealed by a Christmas party.

It wasn’t the firm brochure. It wasn’t the strategic vision. It was the vibe. The lights. The laughter. The sense that this was a place where people belonged to something.

And I’m a sucker for belonging… right up until I’m not.

So I joined.

And I stayed there for ten years.

Ten years is long enough to build a career inside four walls. Long enough to know where the bodies are buried. figuratively… and where the best snacks are kept, literally. Long enough to become part of the furniture, the folklore, and the firm’s internal ecosystem of alliances, unspoken rules, and “this is how we’ve always done it.”

Two years in, they offered me equity partnership.

That’s not nothing.

Equity isn’t just a title. It’s a vow. It’s ownership. It’s a piece of the ship. It’s also an emotional trap disguised as a promotion.

Because once you own something, leaving isn’t just changing jobs.

It’s divorce.

But at the time, I was honored. I took it seriously. I wanted it to work. I tried to make it work. I represented the firm enthusiastically, like I was wearing the jersey, not just playing on the team.

At its largest point, the firm had about twenty-five attorneys.

And I can say this without exaggeration:

Of those twenty-five attorneys, I went to court more than the rest of them combined.

The judges knew me. The clerks knew me. The bailiffs knew me. The security guards knew me.

Some days I’m pretty sure the metal detector recognized my suspenders before I walked through.

I was running hard. Building a department. Carrying cases. Doing the grind. Doing the work. And I did it proudly, because I believed the whole thing mattered.

But here’s what happens when you work inside something big:

At first, the size feels like protection.

Later, the size feels like pressure.

And eventually, the size feels like a room you can’t breathe in.

Tensions rose… not all at once, not in one dramatic explosion.

The named partner, the one who was really in charge, was… let’s just say we saw the world differently.

Different political persuasion.

Different philosophy.

Different approach to leadership.

And during COVID, those differences weren’t theoretical anymore. They were daily. Operational. Policy-driven. Personal.

We butted heads over certain things that mattered to me.

Not “office decor” matters.

Not “do we use the new letterhead” matters.

The real stuff. Values stuff. Integrity stuff. People stuff.

And then it happened.

The lie.

He lied to me about something important to me, something I had a line in the sand about. Not negotiable. Not “let’s revisit this later.” Important enough that once I realized the truth, something in me went quiet.

Not angry quiet.

Determined quiet.

The kind of quiet where the decision is already made and your body is just catching up.

So I started making plans.

Not dramatic plans. Not revenge plans.

Professional plans.

The kind that require spreadsheets, strategy, long walks, and the realization that if you’re going to jump, you’d better build the parachute first.

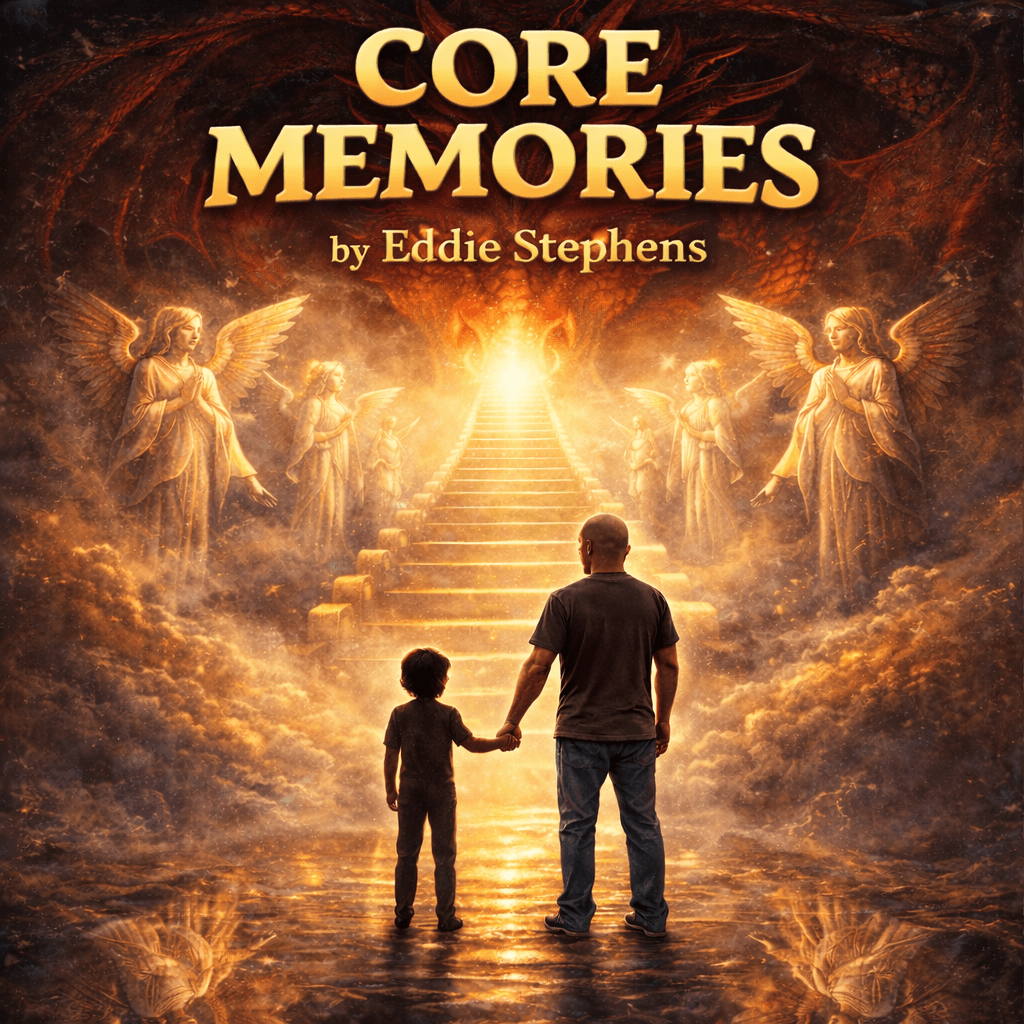

Just before this period I had hired an associate attorney: Caryn A. Stevens.

At first, I gave her the usual associate initiation ritual, remedial tasks, “prove yourself” assignments, the kind of work that’s necessary but not glamorous. Here is some mandatory disclosure to process! The law firm equivalent of peeling potatoes in a restaurant kitchen.

But after six months, I saw it.

Her value wasn’t just competence.

It was character.

She was sharp. Reliable. Hungry. Calm under pressure. Naturally steady, one of those people who walks into chaos and tames it.

And the irony that still makes me laugh: her name is almost the same as mine.

Stevens.

Stephens.

Just swap the V for the PH and suddenly the universe is foreshadowing my future.

At that time, I had no idea Caryn and I were about to forge a new firm that would become the best professional era of my life.

This is also where I met Emily, my trusted paralegal, who has been with me thirteen years now.

If you’ve never worked with a truly elite paralegal, let me explain it like this:

Attorneys drive the car.

Paralegals are the navigation, the fuel, the maintenance, and the calm voice saying, “If you miss this deadline, we all die.”

Emily is the kind of person you build a department around without even realizing you’re doing it. The kind of person who makes the entire machine run smoother, faster, cleaner, and—somehow—more human.

So when it came time to go, it wasn’t just me leaving.

We took the entire family law team.

And some other key employees.

We didn’t just walk out with a box of desk items and a sad plant.

We left as a unit.

I was the first equity partner to ever disassociate from that firm… in thirty years.

That doesn’t make you a traitor.

It makes you an event.

And here’s the part no one tells you about leaving: the real shock isn’t the logistics.

It’s watching people you thought were friends show you the limits of their friendship.

Some said really mean things about me. Some tried to convince Caryn to stay. Some acted like I had committed a moral crime by choosing my own future.

And then, this is my favorite part, the person who mistreated me attempted to be my friend again afterward.

Say what?!?

That’s not friendship. That’s amnesia with confidence.

Like: “Hey! Now that I’ve shown you my ugly colors and tried to damage your relationships, want to grab lunch?”

Sir… You don’t get to throw stones at my house and then ask to borrow my lawnmower.

That experience taught me something valuable: leaving doesn’t just reveal who supports you.

It reveals who only supported you as long as it was convenient.

Caryn and I didn’t leave impulsively. We spent eight months building the plan. Systems, structure, logistics, staff, culture, branding, the whole thing.

Starting a law firm is not easy.

It’s exhilarating and terrifying and expensive and exhausting and weirdly intimate.

It’s like building a boat while you’re already in the water.

And the old firm was very surprised.

They thought I was bluffing.

They thought I’d cool off.

They thought the discomfort of leaving would outweigh the discomfort of staying.

They underestimated one thing:

Once I decide I’m done, I’m done.

After I left, several other equity partners left too. Employees left. Momentum bled out.

And now, that firm no longer exists.

I don’t say that with glee.

I say it as a sober observation of what happens when leadership confuses control with loyalty.

Now… fast forward.

Stephens & Stevens is in its fourth year.

And I could not be prouder.

I’m being fairly compensated for what I do. The vibe is cool. The culture is real. The people are aligned. We’ve hired two associates we’re training. We’re building something that feels like it belongs to us… not just legally, but spiritually.

It’s not perfect, but it’s ours.

And the best part?

I’m not pretending anymore.

I’m not “representing” a system that doesn’t represent me.

I’m not negotiating my values to fit inside someone else’s definition of success.

We are building success on our terms.

Which brings me to the final lesson:

Trying to be in a partnership with seven other attorneys is kind of like a marriage.

Except it’s not one marriage.

It’s eight.

At the same time.

With no counseling.

And everyone thinks they’re right.

And everybody has access to the checking account.

So yes… partnership can be powerful.

But it can also be the most emotionally complicated arrangement you’ll ever sign into with a pen.

I would not suggest it. I sure won’t do it again.

Because I learned the hard way that “bigger than me” isn’t always better.

Sometimes “bigger than me” is just louder than me.

And the real goal isn’t to join something larger.

The real goal is to build something true.

Something that fits.

Something that matters.

Something you can stand inside and still recognize yourself.

And that’s what we did.

That’s what we’re doing.

And I’m never going back.

Leave a comment